When the roof caves in, the water rises, the flames spread or the ground starts to shake, you’re not likely to hear anyone shouting: “Call the researchers!”

But you should hope someone did that last week or last month or the last time this happened.

Decisions made in times of disaster can be the difference between life and death, prosperity and poverty, restoration and ruin. Should you run this way or that? Where do you send the medics? Is it safe to feed the baby donated formula? Do you build a tent city on the town’s soccer field to give displaced people a place to stay? And what about this surge of strangers? Who will coordinate and prioritize the work to be done?

Researchers have asked those kinds of questions around the world in all sorts of situations. They have studied what works and what doesn’t, how human beings are likely to respond and the problems most likely to arise. They can show that decisions and plans based on good information—not just good intentions or a wave of emotion—are more likely to prove their mettle over time.

For more than 50 years, the Disaster Research Center has been that kind of resource, offering field-tested methods, reports and data gathered from around the world in all manner of upheaval—natural and manmade—to anyone who needs it.

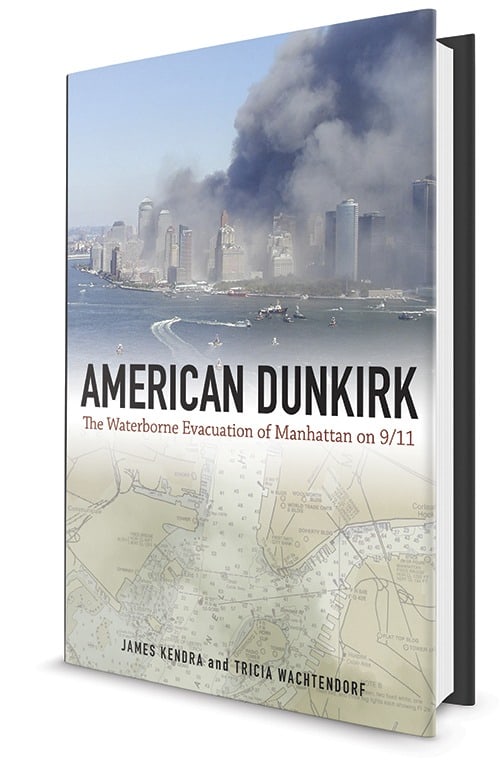

Founded in 1963 by sociologists at Ohio State University, the DRC was a pioneer in the field of disaster research. In 1985, the center moved to the University of Delaware, where founders Russell Dynes and E.L. Quarantelli saw strong support for its mission and further expansion of its role as a trusted source of guidance to planners, disaster managers, policy makers, public health specialists and non-government organizations around the world. In fact, DRC has conducted more than 700 post-disaster quick-response studies since its founding, as well as numerous longer-term studies, according to James Kendra, co-director of DRC with Tricia Wachtendorf. Much of what is known about disaster comes from DRC or its long lineage of alumni and their students.

Its role in the next 50 years will be just as critical when other disasters occur and the world faces problems it can’t even imagine today.

DRC’s ability to connect with experts from many disciplines will be an enormous asset as it has been to Maria Vorel in more than three decades of working in disaster services with the Federal Emergency Management Agency and—more recently—Catholic Charities.

“When you think of resilient communities and how they deal with disasters, it’s not because there are three great people, but because a lot of collaboration is happening across disciplines,” Vorel said. “That’s really what our working relationship with DRC is. DRC helps me to cross channels and disciplines and get things heard on a multidimensional level.”

That means a problem emerging in Nepal may find its answer in a classroom in Newark, a lab in Nashville or an office in Norway.

It happened that way last spring, when government officials from Nepal sought help from an online community of GIS (Geographic Information System) mapping enthusiasts after devastating earthquakes hit the country, which is located in the Himalayas between China and India. They wanted to know if the mappers could tell them which buildings were still standing and which had collapsed—information that would help them respond to areas of greatest need.

Cynthia Rivas, a doctoral candidate in UD’s Disaster Science and Management Program, was among those who stepped up.

“I logged on and started ID-ing buildings for them,” Rivas said. And the professor of the GIS class she was taking invested an entire class period in that same effort.

“That was great,” she said. “You’re not just learning a skill for a résumé, you’re actually doing something.”

As anyone with experience in natural disasters and other crises can attest, “doing something” can be a blessing—as the mappers’ efforts proved to be—or an unintended curse. DRC has collected decades of data to help distinguish what is more likely to be helpful and what is more likely to be harmful, what is based on fact and what is based on myth or misinformation.

The surge of assistance itself can produce problems of another magnitude, with questions of how to manage donations and volunteers and how to make the most of the many agencies and relief organizations that show up to help, each with their own culture and methods and missions.

The numbers were impressive in an article Quarantelli wrote in 2006, citing data the late Joseph Scanlon gathered after a massive industrial fire in Canada.

According to Scanlon, 348 organizations showed up at the plant, including seven local government agencies, 10 regional government agencies, 25 representatives of the provincial government, 27 federal organizations, 31 fire departments, 41 churches, hospitals and schools, four utility companies, eight volunteer groups, four emergent groups and at least 52 different players from the private sector.

Having one central authority to which all those groups report might seem logical to those who want an orderly chain of command, but it’s not necessarily the best approach, Wachtendorf said.

“The whole emphasis on command and control might be effective in small incidents,” she said, “but it doesn’t work when you’re looking at a catastrophe.”

The role of local officials, volunteers, relief agencies and hastily assembled groups of willing helpers often becomes complicated. And when the incident crosses national boundaries, the complexity increases.

The Delaware Medical Relief Team, an informal assembly of volunteer medical professionals who rushed to render aid in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake and in Nepal after its 2015 disaster, encountered many logistical, political and cultural challenges of the sort DRC studies. The center’s expertise can be useful to groups that want to avoid unnecessary problems and build partnerships that contribute to real progress.

Vorel, a sociologist who worked with FEMA for more than 30 years, said it was a relief to have the chance to talk to DRC researchers—as she often did, for example, with Joanne Nigg, DRC’s director when FEMA’s Project Impact was launched in the late 1990s. Project Impact was a novel approach for FEMA, designed to prevent and mitigate disaster at the community level. DRC was hired to evaluate the program’s effectiveness.

“FEMA is not a research organization,” Vorel said. “It is 100 percent practical, short-term response thinking. So it was exciting to have a reputable organization like DRC take on an independent analysis of what we were trying to do. It was a dream.”

The program was successful, and Vorel said DRC offered long-term value beyond that contract’s lifespan. She would sometimes meet Nigg for breakfast just to run ideas by her.

“I could ask things like—‘If I take an existing coalition in the community and spin them up to add this [disaster mitigation work], will it kill the coalition or build it?’” Vorel said. “It was like candy for my brain. And she and I would brainstorm. Just the luxury of taking theory and designing implementation based on that was invaluable.”

Innovative approaches are always on DRC’s radar now.

“One thing we are trying to understand in a more nuanced way is the role of emergent groups and local groups,” Wachtendorf said. “Do they have a seat at the table or someone representing them? In some areas, they may not have a table at all.”

They have significant roles to play, however, and those who dismiss such informal, unofficial groups risk alienating valuable allies.

Wachtendorf and Kendra found examples of innovative solutions that emerged immediately after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. DRC was at Ground Zero two days after the attack and spent two months meeting with emergency management officials and gathering information and insight into the massive collapse of systems and infrastructure.

Providing Reliable Data for Disaster Response Plans

Kendra, whose background is in marine transportation and maritime hazards, said planners can look for such creative solutions to arise in other situations.

Resilience—in people, organizations and systems—is a significant interest for disaster researchers, and DRC is part of an interdisciplinary study of recovery after Superstorm Sandy, which brought mayhem ashore in 2012.

A strong partnership with New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene contributes to that work, which includes collaborators from Johns Hopkins University.

“We are developing both a theoretical model of resilience and recovery and a decision support tool for planners,” Kendra said.

That research team includes a geographer, three sociologists, a physicist, a physician, a health statistician, three civil engineers, a public safety expert and many public health officials, Kendra said.

Tricia Wachtendorf and James Kendra direct the 50-year-old Disaster Research Center, overseeing its work and participating in studies around the world.

Knowledge gleaned aids disaster recovery

DRC researchers have investigated an extensive array of disaster issues arising from earthquakes, hurricanes, tornados, floods, oil spills, fires, hazardous material incidents, plane crashes, riots, tsunamis and terrorism.

The work includes interviews with residents, evacuees, government officials, business owners, medical professionals and many others, review of documents, incident reports and other relevant data.

It is demanding, painstaking work and they don’t rush to every disaster site.

There is no storehouse of survival gear in DRC’s building, tucked behind Graham Hall.

The team uses specific criteria to decide whether to study a particular event, Wachtendorf said, and whether to send a “quick-response team” or wait for a month or more to start fieldwork.

Among its considerations: Does DRC have contacts in the area? Are the logistics needed to reach the site extreme? Is the location relevant to ongoing research? Will language be a difficult barrier?

At times, grant money includes a budget for rapid deployment to a site that would expand research potential in an established project, Wachtendorf said.

Work in the field is invaluable, but it also presents researchers closeup exposure to the heart-wrenching circumstances disaster victims encounter.

Wachtendorf remembers talking to a distraught man on a beach in Sri Lanka after the 2004 tsunami. He had just received his wife’s death certificate.

“We never want to forget that these are real people we are talking to,” she said. “We should be saddened by what they relay. We should feel for them on an emotional level.”

“They have been through so much. But they also want their perspectives heard,” she said. “They have a story to tell and we have a responsibility to listen.”

The encounter with the man, indeed, shed considerable light on the challenges many other men were facing after the disaster. In a country with very strict gender divisions of labor, men who lost wives and sisters and mothers were left struggling with how they would take on this new role caring for their children.

It helps, too, to know that the research goes beyond theoretical and scientific analysis—important in its own right—to applications that improve planning, response and recovery.

That’s the kind of thing that drew her to this sort of research.

“I wanted to make the world a better place,” she said, “but there is no major in that.”

“We are committed to the idea that building knowledge is a kind of humanitarian activity,” Kendra said. “Every place benefits from knowledge learned elsewhere.”

In the aftermath of disaster, officials have little time to consider options and their implications for the future.

“Recovery often brings out conflict in a community that nobody had to tackle before,” Kendra said. “And it forces the community to think suddenly about the future it wants to have. It intensifies the timeframe that otherwise might be stretched out over many, many years.”

DRC offers a trove of data upon which planners and others can build their strategies, with a library of information and research on medical care, mass evacuation, sheltering, logistics, improvised response, preparedness, critical supplies, supply chains, managing donations and volunteers, the needs of people with disabilities, mental health care, community resilience, organizational dynamics, infrastructure security, mitigation strategies and funding, risk management, modeling a range of scenarios including how fire spreads after earthquakes, steps needed to restore water systems, the likely capacity and demand for transportation.

“The nature of our work has shifted to looking more holistically at disaster challenges,” Kendra said.

Journalists often call on DRC researchers for answers and context during times of disaster, which gives further opportunity to share insights with the public and dispel common myths about human response in times of disaster.

Those who anticipate a zombie apocalypse type of scenario, for example—every man for himself—will find no quarter with DRC, where researchers have far more evidence of people pulling together and responding to conditions, not with panic, but with rational decisions and concern for others.

Training future emergency planners

DRC’s work has had significant external support over the years from FEMA, the NOAA Sea Grant Program, the U.S. Geological Survey, the National Science Foundation, Department of Homeland Security, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Collaborators include researchers from around the U.S., Asia, Europe and Mexico, as well as visiting scholars.

Related classes for graduate and undergraduate students are offered in the School of Public Policy and Administration, the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, and the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Alumni of DRC projects now are working in emergency management agencies, public health, disaster planning and related fields, extending the center’s reach even further.

New areas of study and new partnerships continue to emerge, with all manner of inquiry in the mix—intellectual, technical, social, behavioral, cultural. A commitment to working with and learning from diverse populations and team members is vital.

Rivas, the doctoral candidate who helped Nepal with mapping information, said the collaborative nature of the work appeals to her, and that experience will serve her well in the future.

“I have dealt a lot with sociologists, planners, architects, engineers,” she said. “Everybody has their own background and methods to work with. Getting them to work together is very interesting.”

Her hope is to return to her home state, California, and develop something like a West Coast version of DRC.

“I would love to work for a state government and work in emergency planning,” she said.

In the meantime, she continues to work on DRC projects and has joined UD’s student chapter of the International Association of Emergency Managers, which offers educational and service-related opportunities.

“In an era when a lot of suspicion is directed at universities and people are asking what is the point of a graduate or undergraduate education, we can do our part to answer that,” Kendra said. “This is helpful to the University’s mission of graduating students who can tackle these challenges.”

Vorel said she turns to DRC for that reason, too, and contacted Wachtendorf recently to see if any students might be a good fit for an open position in her office.

She sees DRC as a trusted partner, with a depth of knowledge and a proven track record.

The kind of ally you hope for when the world turns upside down.

Mother’s milk is best for babies even in disaster-affected areas

by Beth Miller

What’s a young mother to do? The baby is hungry, the cupboard is bare, the town is in ruins since the earthquake hit and a truckload of donated infant formula has just arrived.

That last part—the free formula— sure seems like good news. What could go wrong?

Plenty, says Sarah DeYoung, a psychologist and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Delaware’s Disaster Research Center. DeYoung is studying how mothers in Nepal make decisions about infant feeding since that country’s 2015 earthquakes and hopes to focus on refugee mothers in the future, as she moves into a tenure-track position at the University of Georgia.

What mothers don’t know about infant formula could harm their babies, she said. And the information they get often is wrong, distorted or incomplete.

DeYoung has made two trips to Nepal since the May 2015 earthquakes that devastated many parts of the Himalayan nation. That same month, she traveled with a DRC team to look at the social impacts of the earthquake in the Kathmandu Valley and rural districts surrounding that area, then returned in November to continue her study of mothers and babies. Her work was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Society for Community Research and Action and the University of Colorado’s Natural Hazards Center. And she consulted with Australian researcher Karleen Gribble, affiliated with Western Sydney University, who found that distribution of formula in disaster-affected counties can affect breast-feeding rates for generations.

A mother faces many challenges in the best of conditions. After an earthquake of the magnitude Nepal experienced, she and her child are especially vulnerable.

So when donations of infant formula start to arrive, a nursing mother in a disaster-affected area might have these thoughts: It’s a formula that many moms in the West use. Many of those nations are richer than my country, so this must be great stuff and I’m getting it for free. If I water it down, I can make it last longer. My sister just used it, and her baby seems OK.

Those kinds of ideas may prompt the mother to stop breast-feeding her baby and use the formula, but that could be bad news for her baby, according to the World Health Organization. The WHO says breast milk is an infant’s best source of nutrition and protection from bacterial infection—no synthetic product has matched it—and it recommends breast milk as a newborn’s diet through six months of age, continuing with other supplements up to the second birthday.

A healthy mother continues to produce milk as her baby nurses, but her body will gradually stop production when the weaning process begins. So a mother who decides to use a bottle may unknowingly reduce her own supply of breast milk.

“One or two instances of giving the baby formula is enough to begin to reduce the mother’s breast milk,” DeYoung said.

The stress of a disaster or other pressures usually doesn’t affect breast milk supply, DeYoung said. However, there is a perception that stress from a disaster causes breast milk to “dry up” or “spoil”—neither of which is true, DeYoung said. There are times, though, that a mother is unable to nurse her child because of injury or illness, perhaps. Some mothers then rely on milk sharing or wet nursing—with their sisters or other women providing breast milk.

Reliance on formula is especially risky in impoverished areas, where formula supply may be inadequate, access to clean water may be limited or non-existent, and preparation may be flawed, DeYoung said.

If formula donations come in packages printed in languages the mother cannot read, she may not know how to properly mix the formula. Adding too much water to powdered formula can put a baby at risk for water intoxication, DeYoung said.

In addition, bottles and bottle teats are difficult to clean and can be a source of disease. Health workers now are recommending cup-feeding even for young infants because cups are easier to clean.

In Nepal, breast-feeding is a culturally accepted norm, DeYoung said. That’s not the case everywhere. In areas where bottle-feeding is common, mothers are not as likely to learn of the benefits of breast-feeding or receive support for it following delivery.

Babies who were bottle-fed before the disaster also need support, but the distribution of ready-to-use formula and support should be targeted to them and carefully implemented by trained health and aid workers.

DeYoung is a mother herself, with a 4-year-old daughter—a fact she believes helps to inform the level of detail in her research questions. She understands a mother’s concerns and routines, and that helps when she is interviewing mothers.

“How is her routine different? How is it the same?” she said. “Every time I go to Nepal I learn something new about the culture and the people. You realize their struggles and then it’s not just the earthquake survivors as one big homogeneous group. There are women and children from different classes, castes and ethnic groups. All of these factors intersect with family structure and possibly decisions about infant feeding.”

MORE STORIES

Energy IQ

Put your Energy IQ to the test, and let’s see if you are an energy guru or a fossil fool.

Catalysis Center for Energy Innovation

Cool video highlights CCEI’s mission of turning cornstalks and wood chips into fuels, electricity and chemicals.

Scanlon papers now part of disaster resource collection

T. Joseph Scanlon, a respected journalism professor in Canada, had a long-time relationship with the University of Delaware’s Disaster Research Center, which is now the repository of his over 70,000-piece collection.

Honors

The UD community celebrates its first Gates Cambridge Scholar, two new fellows in the National Academy of Inventors, and the first woman to receive the Soil Science Society of America’s Kirkham Soil Physics Award.

News briefs

A humanoid robot joins the pediatric rehab team, a new UD study suggests online shopping may not be as “green” as we thought, a professor aims to improve student experiences in global health, and summer research all-stars take the field.

Keeping a killer flu in check

Who do you call when bird flu comes knocking? UD’s Avian Biosciences Center is working to contain the threat of bird flu—locally and globally.

Research Magazine Survey

We value your opinion. To show you how much, we will award a $100 Barnes & Noble gift card to three people who complete our survey. To be entered in this random drawing, please complete the survey by Nov. 1, 2016.

UD Authors

In her award-winning book, historian Christine Heyrman explores how the first U.S. missionaries in the Middle East influenced a nation’s attitudes toward Islam.

What science writing can teach us

Journalist, author and UD’s Distinguished Writer in Residence Mark Bowden shares lessons he learned as a science writer and recent samples of his students’ work.

New Train Station Project on Track for STAR Campus

An upgraded transportation hub in Newark will bring new riders and serve as an anchor for UD’s 272-acre Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus.

Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes…

With significant change all around us, Delaware’s leaders—including the University of Delaware—are working to turn adversity into new opportunity.

Fueling the quest for green energy

Turning cornstalks and wood chips into renewable energy and valuable chemicals isn’t easy, but it is a promising focus of research at the Catalysis Center for Energy Innovation.